General News

9 January, 2025

Father felled and forgotten without family

By KEN ARNOLD THOMAS Whyte’s dreams were many when leaving family behind for a golden adventure in colonial Australia. Leaving all he knew and loved in Scotland, Thomas Whyte boarded a ship bound for Port Phillip intent on making a living in...

By KEN ARNOLD

THOMAS Whyte’s dreams were many when leaving family behind for a golden adventure in colonial Australia.

Leaving all he knew and loved in Scotland, Thomas Whyte boarded a ship bound for Port Phillip intent on making a living in Melbourne, the plan for his wife and two children to sail across the seas and the family to be one again.

The grand reunion of family Down Under was not to happen. Instead, the dour Scotsman had his life cut short on the Korong goldfields where he was buried in an unmarked grave at the side of the road.

A mere five years after leaving his family behind in Edinburgh, Whyte succumbed to rheumatic fever. Tragically his family had not yet been able to join him in Australia and remained across the world, left with only letters to remember their adored father and husband by.

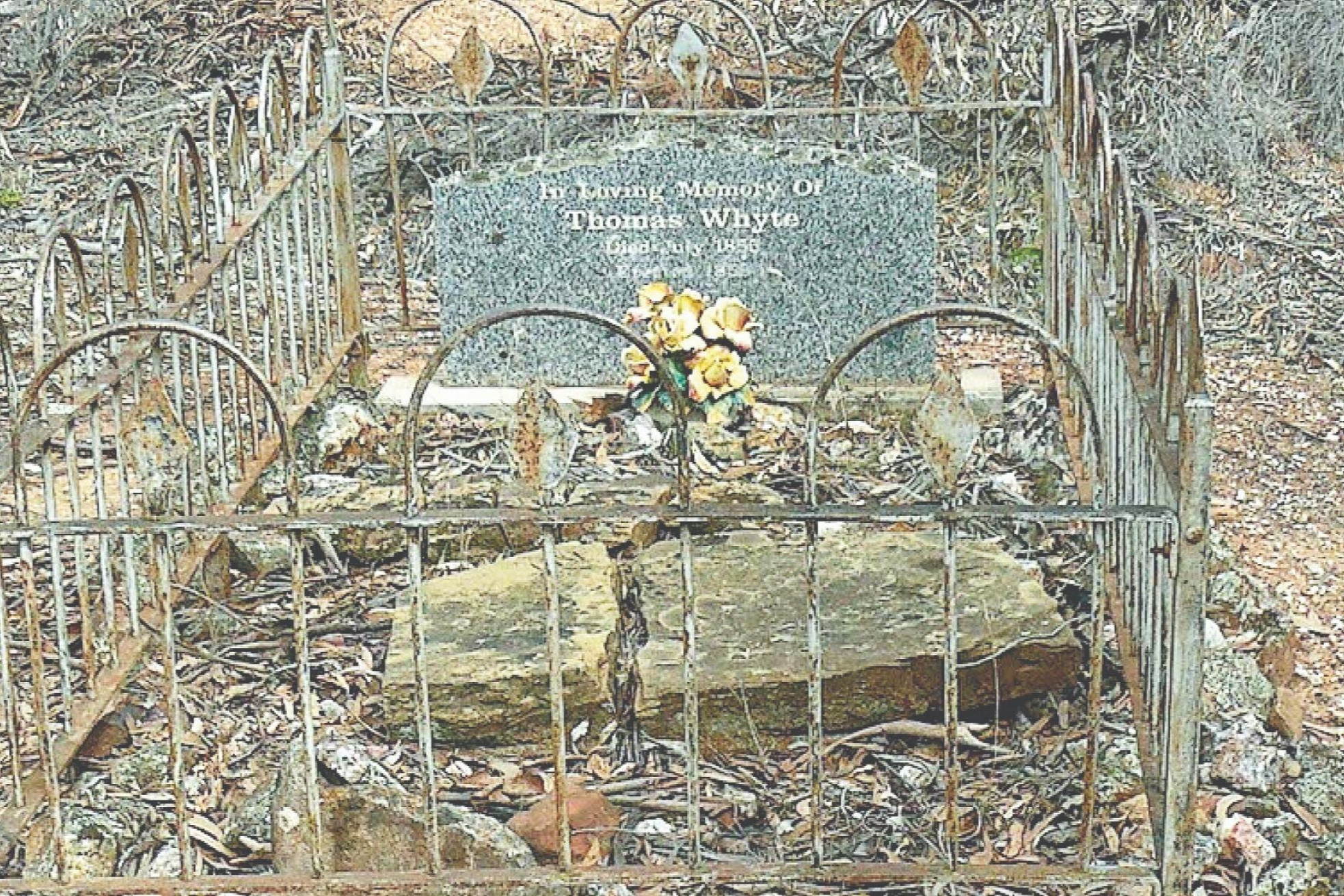

With Whyte’s wife and two young children on the other side of the world they were unable to arrange cemetery burial rites. Instead, Thomas was buried by fellow miners in the bushland of Wedderburn, alone, as his grave remains to this day, marked only by an ornate fence and a recently added headstone, hidden in nature.

Thomas Whyte, born 1814, Edinburgh, Scotland, married Jessie, the second daughter of George and Jessie Duncan, and to them were born Robert, September 1842 and a daughter Jessie.

Thomas emigrated in June 1850, arriving at Port Phillip Bay after almost four months at sea, in late September. Once Whyte had arrived in Melbourne, he hurriedly penned a series of letters to his beloved children:

“My dear children, I arrived here last Monday all safe, well and happy, after a most delightful voyage of three months and a half. I had written a very lengthened account of the voyage, but as this is to go by the Overland Mail, I shall send it to you next time when you will hear of all the different sights and events that happened on my way.

“I shall write you very often and hope you will write me of all that happens to you, how you are getting on in your education, who are your companions and everything else that interests you. In future I will write to each of you separately but as this is merely a few lines to tell you of my safe arrival I will not enter into particulars now.

“The place where I have come is a most beautiful place, the kindest of people, the finest climate and everything to make anyone happy. The vine and orange grow in the open air and some bending over the cottage windows. Parrots and cockatoos hop about and chatter to each other like human beings. Goats feed about the streets like dogs at home and everything in nature is pleasing.

“The natives in the bush a few miles from town are seen in the wild state of former times, with their kangaroo skin thrown over their shoulders and nothing else, their spears and boomerang with which they hunt their game, they are very picturesque.

“Everything here is in plenty, no want, no beggars, no starving, the best of butcher meat one penny per pound and everything else in proportion – everyone appears to be happy and pleased and doing well.

I have got a nice shop in the best part of the town which I enter tomorrow where I hope to do well and make money that I may be enabled at the time that I promised to come and see you – for my heart’s desire is for your good and to see you again with me as in olden times is what I will strive for; there is every prospect of doing well here, and when I write you, I shall always tell you my wishes and intentions. I parted from you both very shortly in Edinburgh, but I hope the next time we meet we part no more in life, for we will be together again and be very happy.

“My dear, dear children my heart is completely bound up in you and I sincerely trust that we may all be spared to meet again in health and strength and be united in our happiness. I am far from you, but I remember you nightly at the throne of grace and hope, young as you are, you will do the same for me; we can all meet there daily, however far parted we are. I sincerely trust you have both been in the best of health and that you are doing all that lies in each of your powers for your future advancement in life.”

“I shall write to you at much greater length next time, as I have now merely time to get the mail at present. Your letters you will give to your aunts in Edinburgh, or sent them to your uncle in London direct and he will send them to me; and do not delay writing until you hear from me but always try and write me once a month and I will do the same from here, telling me all your little matters and everything that concerns you for that to me will be most interesting.”

At that time both his children were at boarding schools, Robert at George Watson’s, and Jessie at Merchant Company’s school. Whyte must have been of reasonable means as he mentioned he had purchased a shop at 6 Collins place, Melbourne from which he would sell clocks, jewellery and smokers’ pipes which his brother Robert shipped out to him.

Part of letter that Whyte wrote, dated November 12, 1850, reads: Everybody has got goats here and the large cockatoos of all colours, perched on poles at lots of the doors in the street. The wagons and carts are all drawn by oxen and when they come down from the country with the wool there will sometimes be twenty teams following each other, each having twelve or fourteen bullocks pulling them along – the bullock drivers with their blue frocks and big straw hats shouting their strange cries, with the tinkling of the bullocks bells hung around the yoke – a few natives with their opossum skins pinned around them, their black curly hair, with a whole host of dogs at their heels, make the scene rather picturesque to one who has lately left Cornhill and Cheapside.

But mind, although there are many things rough, still there is a strong struggle going on for civilisation and improvement. There are more churches and scientific institutions with literary reunions than is to be found in any town in England for the same population. People are dressed in the latest style of fashion, and you will see more well-dressed people in church than is to be seen anywhere at home. It is a splendid place this for the working people; ordinary tradesmen like carpenters and masons get two guineas a week, and shepherds and bullock drivers, their board and lodgings and thirty pounds a year. No-one need starve here and there is full employment for everyone one that likes to work, and everyone does well, it is one of the most thriving places in the world.

Whyte’s eldest son, Robert Whyte, aged nine, wrote back on February 1, 1851, sharing his achievements with father and lamenting the distance between them.

“Last year I got three prizes, one for English reading, one for Latin and one for Sabbath day lessons. I would have written sooner but not receiving your letter from you I was not sure of your arrival. I hope, as you wish me, to write you monthly after. Jessie would have written you today, but a rash came out on her throat yesterday so she was sent up into the sick-room and so she did not get out today.

“I am dux in English reading, third in Latin and second in counting. There is one of the boys in particular that I play with whose name is William Hill and another Alexander Frier. I am very happy that you have landed, it is so very nice. I am glad that you have got a nice shop and place for it. I think it must be a very nice thing to hear cockatoos and parrots chat, and to see the orange and vine grow in the open air and to take them without paying anything must be still more pleasant.

“I am always thinking about you and wishing I was with you; I am sure I wish either I was beside you or you were beside me. I am learning my lessons as well as I can so that I may be able to help you in the shop. It makes me very happy to think of you.”

It was not long before exodus from Melbourne to the Bathurst, Ballarat and Bendigo goldfields began hence Whyte began to suffer business wise. It would appear that Whyte closed his shop and headed to the Maryborough area, probably Chinaman’s Flat rush, before moving onto Wedderburn in 1854, where he worked as miner.

Tragically in 1855 Thomas Whyte contracted rheumatic fever from which he never recovered, and died on July 21, oceans away from his beloved family.

William Cosh signed an affidavit, in the presence of Hal Webster JP, which stated that he often visited Whyte and had noticed that he was ailing before passing away on July 21, 1855. The affidavit also contained the observation that Whyte was 5 feet 7 inches tall, had a ruddy complexion and a prominent nose.

As there was no registrar in the area Cosh, helped by Richard Donaldson and William Martin buried Whyte close by to his tent. A sandstone monument was put on the grave which has an ornamental fence. The headstone has been replaced in recent times. To find the grave of Thomas Whyte head north out of the town before turning right into Tantalla Street, proceed to the Y intersection veering left into Bernara Street, keep following the road until you come across the site on the left-hand side.

Widow Jessie Whyte lived for another 40 years in Edinburgh. She died in 1895.